PROVOCATEUR: Fairey’s root formula is the classic pulp combo of bad-ass guys and sexy gals. |

Shepard Fairey and his crew of three punky glue-spattered assistants (plus an art curator) pour out of a maroon mini-van and unload buckets of paste, brushes, a ladder, and a wheeled suitcase full of his screenprinted posters onto the sidewalk. It’s around 2 pm on a sunny, crisp October Monday. And the guys are preparing to poster two walls in bustling Harvard Square.Fairey is one of the most famed street artists (the refined term for people who do what used to be known as graffiti) in the world. His work seems to be everywhere these days — and it actually is in the case of the iconic red-white-and-blue Barack Obama “Hope” poster that he produced this spring. The 38-year-old Los Angeles artist first gained notice nearly two decades ago as a student at Rhode Island School of Design when he began (illegally) plastering Providence — and then the world — with stickers featuring the wrestler (and actor in the 1987 film The Princess Bride) André the Giant. Later versions were amended with the word “Obey.”

“I realized that getting people to question all the imagery they’re inundated with daily,” Fairey says, “was something that was actually somewhat important to, I think, the way people communicate, and the way people can either question the use of public space or just passively submit. So then that’s why the idea of making an image that confronted people with the idea of obedience.”

Fairey is in Boston to check in with the Institute of Contemporary Art, which is scheduled to present his first solo museum show in February. “It’s now been almost 20 years that I’ve been doing street art, and using street art both as a way to showcase my art and put my politics across and I guess bypass the bureaucracy of the gallery system. Now I’ve been embraced by the gallery system, but it wasn’t because I pandered to the gallery system. It was because the gallery system relies on supply and demand, and I created a demand for my work by doing street art.”

While he’s in town, the ICA has lined up officially approved spaces for him to poster: a Montgomery Street fence in Boston’s South End; the International Bicycle Center in Allston; the boutique Grand in Somerville’s Union Square; the graffiti wall around the corner from Central Kitchen in Cambridge’s Central Square. I meet Fairey’s crew at a red brick wall outside the Gap at 15 Brattle Street, which the Harvard Square Business Association has helped arrange permission for them to poster. Fairey is dressed in blue jeans, Adidas sneakers, and a black hoodie that he removes to reveal a black T-shirt bearing the slogan “Bone: thugs-n-typography.” He has shaggy graying brown hair and a raffish scar running up his left brow.

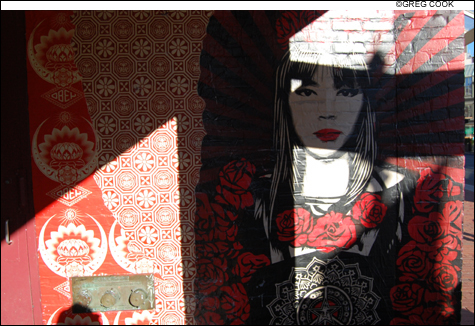

Fairey has sweet-talked a lady from the HSBA, telling her that where he puts a piece often dictates “how antagonistic I’m going to be,” and that the one outside the Gap will be a not very antagonistic pro-peace image. It depicts an Asian woman wreathed in roses. A star featuring the looming features of André the Giant covers a peace symbol on her chest. Referring to the iconic “flower power” photo from the 1967 March on the Pentagon, he says, “I always look at . . . the flowers at the end of the guns, to me flowers are always about peace.”

The crew wallpapers the bricks to the left of the rose-lady poster with posters featuring an Islamic interlace pattern based around an André-star motif and posters featuring a moon crescent holding a lotus blossom plus André and “Obey” logos. (His work is rife with self-promotional logos.) Fairey is careful about details — he and the crew use paint to touch up bits that don’t line up and spray-paint missed edges.

His bold, simple graphics ape styles and colors (red, black, white) of Soviet and Maoist propaganda, pop Che Guevara graphics, rock-concert posters (’60s psychedelia, the Misfits skull), and American money. It seems that last year decorative Islamic-style patterns crept into his designs. But his root formula is the classic pulp combo of bad-ass guys and sexy gals. The posters offer cool catchy looks and fiery political slogans, but they leave an odd aftertaste, something like when hip songs are used to advertise compact cars.

The crew moves up the street to 3 Brattle, the former Greenhouse restaurant, which is boarded up while being converted into a bistro. They flank the door in the middle of the façade with a pair of perhaps seven-foot-tall posters. The one on the right features a soldier standing atop a grenade surrounded by slogans: “World Police/More Military/Less Skools/State Champs.” The one on the left shows a hand holding up a gas nozzle in front of an eagle and the slogan “Operation/Oil Freedom.”