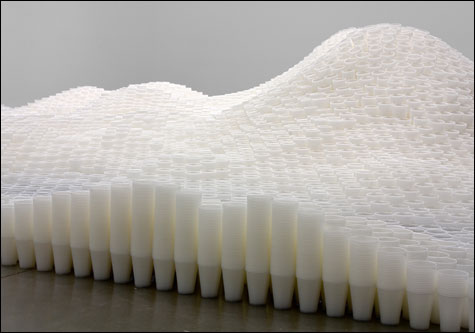

UNTITLED (PLASTIC CUPS): Sometimes Donovan suggests a mad-scientist Martha Stewart tinkering

in her cellar late at night. |

| Tara Donovan | Institute of Contemporary Art, 100 Northern Ave, Boston | Through January 4 |

Turn the corner into one of the final galleries of Tara Donovan’s new show at the Institute of Contemporary Art and you come upon a giant cell-like thing bulging and bubbling down from the ceiling. Its ingredients sound mundane: Untitled (Styrofoam Cups) (2004/2008) features hundreds of Styrofoam cups hot-glued side to side and hung from above. But somehow these cups — and you can always tell they’re cups — become something else. They’re lit from behind so they seem to glow. And as you walk below them, they resemble clouds or, as Donovan has said, “ice that covers a lake or ocean, but you’re underneath that ice, looking up.”

Last month, the Brooklyn sculptor was named a MacArthur Fellow — that is, she received what’s known as the $500,000 “genius grant.” Here you can see why: her sculptures are filled with surprises as she finds the extraordinary in the ordinary, turning masses of quotidian materials like styrofoam cups into gee-whiz sculptures resembling bubbles, rocks, seas, and other forces of nature. They seem like something dreamed up by a mad-scientist Martha Stewart tinkering in her cellar late at night. They radiate the satisfying certainty that of course disposable cups or toothpicks or drinking straws have this amazing secret life when they’re not working their day jobs, and that of course this is what they were always meant to do even though you’ve never seen them do it before.

Organized by ICA curators Nicholas Baume and Jen Mergel, the exhibit, the first museum survey of the 38-year-old’s career, assembles 16 pieces from 1996 to 2008. Like the ICA’s Anish Kapoor survey this summer, it’s one of the best shows seen around here this year. Perhaps the ICA has found its footing and is on a roll after a mediocre first year in its new building.

One night, back in the mid 1990s, Donovan was making porcupiny sculptures by sticking potatoes full of toothpicks. “At one point, I accidentally knocked over a box [of toothpicks],” she recalls in the exhibition catalogue. “And for whatever reason, instead of just scooping it up or whatever, I pulled the box off and the toothpicks inside held the [shape of the] corner.” It was her “Aha!” moment: if toothpicks stuck together this way, maybe she could build cubes of them that would be held together just by “friction, gravity, weight, interlocking.” She ran out to buy all the toothpicks she could find; when that wasn’t enough, she ordered cases. She fashioned a “slumpy” foot-square cube and over the next month scaled up to about three feet, realizing that bigger held together better. (“It’s strong enough even for me to be able to stand on top of it.”)

In the process, she felt her way toward her signature mode of making art. “It’s really so much about isolating a material and then doing experiments with it,” she tells me at the ICA. “Those experiments can sometimes get figured out in a day; sometimes it takes months. There’s not a specific set answer. I’m looking for the material to reveal some kind of phenomenological aspect that is kind of beyond anything I could do to it by manipulating it. Where it kind of takes on a life on its own. That’s what I’m looking for. That transcendence.”