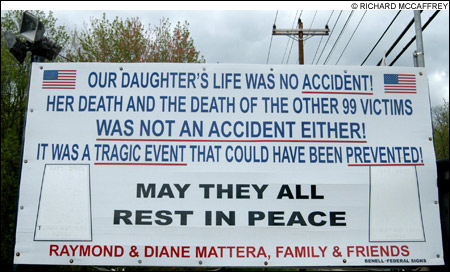

TERRIBLE LOSS: While relatives of the victims have made clear their feelings, they don’t appear to have organized a political response.

|

It was perfectly understandable that Bill Harsch was reluctant to answer the question.

At midday last Friday, September 29, relatives of the 100 people who perished in the Station nightclub fire were still sharing their heart-rending tales of loss at the Kent County Court House in Warwick.

It was a searing reminder for anyone listening — the court proceeding was carried live by local TV and radio stations — of just what a raw wound the February 2003 disaster remains for the hundreds of people touched by it. Adding insult to injury for many of these individuals was the plea bargain that short-circuited the possibility of a trial for Station co-owners Jeffrey and Michael Derderian, not to mention how Jeffrey Derderian was spared a single day in prison.

As we talked that day in his downtown Providence law office, Harsch was keenly aware of the anger and bitterness about the plea bargain — to the point of questioning the timing of our interview — although he demurred when asked about the direction of this welter of emotion. A day earlier, the Republican challenger to Attorney General Patrick Lynch had staged a news conference, charging that Lynch was either attempting to duck responsibility for the plea bargain or had lost control of the prosecution of the case. But now it took some warming up on other elements of his campaign message before Harsch would comment on the biggest news of the day, prefaced by an obligatory disclaimer: “I’m not thinking politics here.”

However unsavory it might seem for a candidate to acknowledge the political implications of the Station plea bargain, the resolution of these criminal charges will hover over Lynch and Harsch, in different ways, in the slightly less than five weeks until Election Day. Lynch has steadily made himself available to talk about the case, but he probably can’t wait for it to go away; Harsch desperately needs a big issue, but he may be incapable of seizing the moment.

The nightclub disaster is an extreme example of how, because of the contentious cases that invariably land on the attorney general’s desk, the office has long been a graveyard for politically ambitious officeholders in Rhode Island. (Thanks be for Sheldon Whitehouse, almost four years have passed since the Democratic challenger to US Senator Lincoln Chafee was AG.)

At best, the bitterness and frustration about the plea bargain might help someone to build support for a classic outsider challenge to the Democratic incumbent.

But that someone doesn’t appear to be Bill Harsch.

For starters, the GOP challenger’s tentative response last week reflects the inherent difficulty in trying to gain political advantage from an unmitigated tragedy. While Harsch vows to do everything possible “to see that the truth comes out,” and, if elected, to review the case, the suggestion that he’ll be able to do something substantial is questionable. The criminal case has been settled, and nothing’s going to change that.

And as it stands, Harsch — who has a much smaller war chest, and who remains far less well known than Lynch — has a lot of ground to make up, as demonstrated by a Brown University poll, conducted before the plea bargain became public, which showed Lynch with a commanding 57 percent-24 percent lead (the results were almost identical to the findings of a June poll).

The wild card in all this is the relatives of those who died and of the hundreds more who were injured in the West Warwick nightclub fire. Yet while many of these people have made clear their anger with Lynch and Judge Francis Darigan in particular, and the criminal justice system in general, there doesn’t appear to be an organized response.

Speaking last week on RI-PBS’s A Lively Experiment, David Kane, who lost his 18-year-old-son, Nicholas O’Neill, in the Station fire, and who threw his support to Harsch after contemplating a run against Lynch, said the family members of those who perished remain so devastated that they haven’t been able to get together, politically or otherwise.

From bad to worse

Considering the magnitude of the devastation, there was bound to be some severe dissatisfaction with the outcome of the criminal charges in the Station case. Yet the development of a pervading public sense in the aftermath of the plea bargain — of a lack of official straight dealing — managed to make a bad situation worse.

Harsch had avoided comment in the run-up to the apparent trial, “[but] the situation changed when the whole thing went off the rails with the plea bargain fiasco,” the challenger says, in rolling out his message. “I am the alternative to Patrick Lynch and I want the people of Rhode Island to know that they have an alternative.”