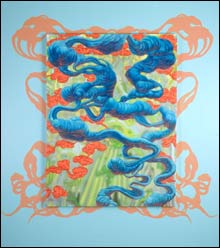

ECSTATIC BEATIFICATION: Cristi Rinklin’s spaces evoke the flashing, artificially flavored hollowness of the Internet. |

During the early ’90s, DeCordova Museum curator Nick Capasso was telling me recently, “Abstract painting was really moribund, really boring, particularly in Boston.”At the end of modernism, the style of bravura painterly abstraction flowing out of the work of Willem de Kooning had come to seem egotistically melodramatic. And the abstractions of cool flat shapes and stripes flowing from Barnett Newman and Frank Stella seemed hollowly formal. The postmodernist stuff that followed seemed caught in a feedback loop of art about art, narrow formal games, and wink-wink pastiche.

But Capasso noticed Thaddeus Beal of Somerville: “Here’s this guy who’s making these paintings that are very complex, and based on fractal geometries and chaos theory.” It seemed like the beginning of something new in abstract painting. And over the past decade and a half it’s become a certifiable trend.

The DeCordova Museum’s grandly titled new “Big Bang! Abstract Painting for the 21st Century” rounds up 15 painters, mostly from New England, who reinvigorate abstraction by looking outside the narrow confines of art and drawing inspiration and imagery from computers, stars and constellations, quantum physics, data mapping, the Internet, genetics, squiggly microscopic critters. This is Information Age abstraction, thrilled by the wonders of all our fantastic new technology even as it notes that technology — computers, microscopes, telescopes, even animated cartoons — is ever coming between us and the natural world.

That’s not to say it’s scientific. “Sciency” might be a better word, because though this stuff evokes science, it’s mostly pretend. It’s fascinated with the “idea of data,” as one wall text smartly notes, but it imagines its own worlds rather than getting hung up on the real thing.

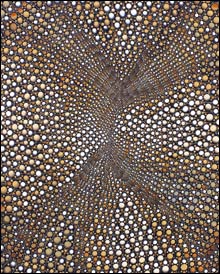

One dazzling example is Williamstown artist Barbara Takenaga’s paintings of what often look like radiating, spiraling galaxies. In Angel (2006), pulsing orbs stream inward, the currents seeming to fold and kiss in the center. These paintings are mesmerizing, like ’60s psychedelic rock posters or op art. They evoke the awestruck, overwhelmed feeling we get when contemplating the vibrating vastness of the universe, but they’re not star maps you could chart your rocket by.

ANGEL: Barbara Takenaga imagines her own worlds rather than getting hung up on the real thing. |

In the paintings of Cristi Rinklin of South Boston, plumes of blue and red smoke meander through vast airless theatrical spaces that evoke the flashing, artificially flavored hollowness of the Internet. Much as Ellsworth Kelly finds the geometric shapes for his monochromatic abstractions by isolating the shadows of trees or the stripes of beach cabanas, Rinklin builds her abstract realms by collecting snippets of digital flora and fauna. These are hand-painted works that come out of Photoshop, which she deploys to twist and stretch, blur and layer her source images of Baroque painting, cells, constellations, and natural-history illustration.

Bostonian Julie Miller’s amazing obsessive-compulsive doodle o(1) from 2006 is a giant field of teensy orange circles drawn with needle-pointed pens and topped by weaving lines that lasso bull’s-eye green circles. Pink and yellow paint-marker dots hide camouflaged in the pattern; here and there magenta dots pop out. Miller’s drawings always remind me of microscopic views of circulating blood cells or skin, but a monitor plays her o(15) from 2006, a continuous animation of fields of tiny circles that looks like buzzing TV static.

Painting is a slow medium, a medium built for mulling. This makes it a good place to consider today’s instantaneous, ever-moving technological world. But despite topical references to science and digital imagery, this art isn’t really about taking on these subjects. It’s art about beautifully replicating their visual effects. Abstraction here is a way to avoid engagement.

Painting also inevitably calls up associations to its long history. The most pervasive — and surprising — correspondence in these artists is to Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings. Pollock’s work has been seen as a dead end, too much of a signature gimmick for anyone else to adopt. But here are Pollocky swirling lines, obsessive doodles in all-over patterns, even drips.

Steven Bogart of Maynard mimics Pollock’s technique directly with webs of poured paint atop soft backgrounds polka-dotted by clouds of color. Thaddeus Beal scratches radiating geometric patterns into putrid yellow fields in a meditative, Islamic patternwork echo of Pollock’s all-over designs. Jon Petro of Worcester builds large painterly abstractions from accumulations of lots and lots of scrawled ovals. Meg Brown Payson of Freeport, Maine, pours and blots watery, semi-transparent circles of paint to create elegant designs that could be images of cells under a microscope or coffee-cup rings. It’s as if Pollock had painted restrained abstract watercolors. Providence artist Terry Rose adds ink and pigment into wet varnish so that the colors bleed out naturally, assuming delicate organic shapes. The results resemble speckled wet sand at the edge of an outgoing tide, constellations, the gleaming insides of shells, green jellyfish drifting in a silver sea, an exploding sun. The cosmic motifs remind you that Pollock’s first drip paintings in 1947 were titled Galaxy, Reflection of the Big Dipper, and Shooting Star.