TV BUDDHA: Nam June Paik suggests a mystical eternal present — by turns funny, eerie, and

mind-blowing.

|

|

“Charles ‘Teenie’ Harris: Spirit of Community” | Gallery Kayafas, 450 Harrison Ave, Boston | Through December 29 | “Sounding the Subject” and “Video Trajectories” | MIT List Visual Arts Center, 20 Ames St, Cambridge | Through December 30

|

Some call Charles “Teenie” Harris’s five decades of photos of Pittsburgh one of the grandest chronicles of African-American life ever assembled. Harris was an African-American newspaper photographer who worked primarily for the African-American press; that helps to explain both his achievement — which is surveyed in the current 40-photo exhibition “Spirit of Community” at Gallery Kayafas — and the general ignorance of it. Only in the past decade — following Harris’s death in 1998, at age 89, and the Carnegie Museum of Art’s acquisition of much of his archive in 2001 — has the art world begun to take notice.

It’s said that Harris’s brother, for whom he had run numbers for underworld gambling, gave him the money to buy his first camera in 1929. Before long, his photos were being published in the weekly black-owned Washington magazine Flash!, and they attracted the attention of the Pittsburgh Courier. The Courier was an internationally distributed newspaper produced by and for African-Americans at a time when the white press mostly ignored black life. In the first half of the 20th century, it was one of the leading voices advocating civil rights, especially for African-Americans who were fighting for their country in World War II. The paper aimed to show the African-American community at its best.

Harris began shooting for the Courier in 1936, and he photographed for it until he retired in 1975. The fight for civil rights percolates through his work. African-American women picket a deli that doesn’t hire black counter clerks. An old black woman holds Nazi signs that read, “Kill all blacks.” Jackie Robinson, in a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform, leans on a bat at the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Forbes Field in 1947, the year he broke into major-league baseball.

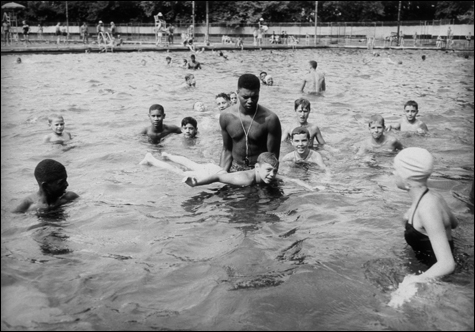

SWIMMING INSTRUCTOR AT INTEGRATED POOL, C. 1959: Harris’s photo embodies the very

moment of transition from one era to the next.

|

In one magnetic photo, black and white boys and girls play together in an integrated swimming pool, probably in the 1950s. The Carnegie Museum’s description of this photo suggests it depicts the very day the pool was integrated. The scene is charged by the ambiguity of the relationship between the black lifeguard at its center and a white boy who’s learning to swim. Is this young African-American subservient to the white kid he’s cradling, or does he enjoy the authority of a teacher and guardian? Are we seeing racial differences bridged, or the same old hierarchies? The photo seems to embody the very moment of transition, with all its hope and nervous uncertainties, from one era to the next.

Harris photographed celebrities who rolled through town: President John F. Kennedy, boxer Joe Louis, jazz greats Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Billy Eckstine. But most of his photos show anonymous slices of life in his neighborhood, Pittsburgh’s Hill District (where most of August Wilson’s “Pittsburgh Cycle” is set). Four elderly women sit on a porch swing. Men and women line the counter of bar. A girl sits atop a pile of newspaper bundles. A soda jerk draws a drink. People crowd a street for a parade. The scenes, now burnished by nostalgia, are fascinating because of their ordinariness. Few other photographers were paying attention to everyday urban African-American life then, let alone amassing more than 80,000 photos. (Harris scholarship remains in its infancy, so much of the who, what, where, and when remains to be documented.)

Taken one by one, his photos are hit or miss. People will line up and mug as if for a school-yearbook photo. (A shot of kids lined up in the spray of a fire hydrant is a witty variation.) But his directing (or what I imagine is directing) could also be more subtle. Men gather on the sidewalk outside a candy-and-cigarettes shop playing checkers — it looks as if Harris had just happened on the scene, but note that the on-lookers crowding around the gameboards all conveniently stand behind them so as not to block Harris’s view.

It’s when his work is seen as a whole that Harris’s achievement comes into focus. As a photojournalist, he’s set apart by his connection to his subjects. He’s an insider portraying his own neighbors, and that gives his work the warmth and familiarity of family photos. Sometimes his photographs even remind me of Norman Rockwell — in a good way. The two men share a generous, amused, empathetic eye that’s apparent in Harris’s shot of an officious young crossing guard halting a group of kids at a sidewalk edge, or his photo of a tiny boy in too-big boxing gloves sitting in the corner of a boxing ring forcing a smile as a tear rolls down his cheek. But the connection is bigger than that. At the heart of both artists’ work is an optimistic vision of community — and perhaps America — as a nourishing, tolerant, welcoming place. These images may depict our many difficulties and divisions, but they bring out our best selves.