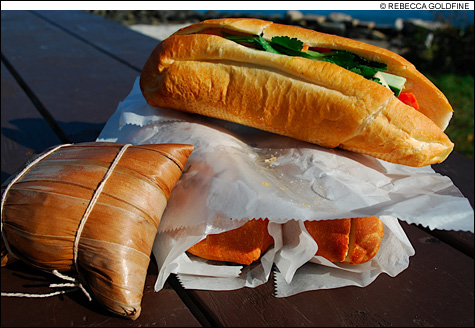

CRISP AND TASTY: A bánh mì from Kim’s Café. |

| Kim’s Café | 261 Saint John St, Portland | daily, 9 am-6 pm | no credit cards | 207.774.7165 |

The most unpleasant things can have surprisingly pleasant unintended consequences. One example is the French occupation of Vietnam, which nevertheless produced the bánh mì sandwich — a good version of which is available here in Portland at Kim’s Café. It’s not easy to explain how pleasant it is to walk into Kim’s. The proprietress keeps up an effortlessly friendly banter. The back of the store offers the designer clothes Sarah Palin favors, but at low prices. The lunch available up front costs half of the typical sandwich in this town.While the charms of Kim’s are ineffable, we can explain why the occupied Vietnamese invented such a delicious sandwich. System justification theory argues that expectations of conflict between social groups are misguided. Most people, most of the time, are interested in maintaining the status quo in the most palatable way possible. Subordinate groups in particular, having cobbled together survival strategies under difficult circumstances, rarely expect changes to the status quo to work out in their favor. If someone has the means to crush you, you try to keep them happy.

This explains why, before he stumbled upon the amalgam of charisma, determination, and political genius that helped drive out his country’s occupiers, Ho Chi Minh spent his youth mastering the art of French baking. It also explains the charms of the bánh mì — a sandwich whose eagerness to please French palates borders on the satirical. It is as if someone had taken a comic-book version of French tastes — crusty baguettes, crisp crudité with mayonnaise, sweet butter, roast pork, creamy paté — and stuck them together in a desperate attempt to ingratiate.

The attempt succeeds. A Kim’s sandwich comes on the sort of simple French baguette with a sweet, yeasty, chewy charm that is almost lost in this era of seedy whole grains and wraps. Kim’s lightly toasts the outside, so that the soft inner surface is left ready to soak up the buttery mayonnaise and thin scallion sauce. While some shops dice their vegetables small, Kim uses big crunchy spears of fresh cucumber and carrot, along with shreds of pickled radish, big sprigs of cilantro, and a few thin slices of jalapeno.

Unless your bite hits a pepper — which imparts a sharp verdant heat — the dominant flavor of Kim’s bánh mì is sweet. They don’t overdo the meat, which keeps the sandwich from feeling heavy and lets the other ingredients sing. Semi-thick slices of roasted pork are mild so they don’t overwhelm the vegetables, and add as much to the texture of the sandwich as the flavor. The smear of paté that comes on some sandwiches is more sweet than liver-sharp. The combination sandwich offers that paté with a few different thinly sliced cured porks — a bit like an Italian sandwich with less spicy meat. The shredded chicken is moist and tender, having soaked in a mild vinegary sauce. The barbecue beef was saltier and chewier than the other sandwiches. The vegetarian, which features soft rice noodles and tofu, takes the sandwich in a softer and even sweeter direction.

On weekends Kim’s offers more complicated Vietnamese specials. We liked the banh-gio, with a quail egg hiding amid diced pork and mushroom inside a big rice-flour dumpling moist within a banana-leaf wrap. Vietnam, where conflict eventually broke out despite the bánh mì, offers complex lessons as well — worth contemplating as we ponder electing a veteran of that war.

When a few incendiary bombs exploded on a ship’s deck, a young John McCain told a reporter, “Now that I’ve seen what the bombs and the napalm did to the people on our ship, I’m not so sure that I want to drop any more of that stuff on North Vietnam.”

But he dropped more, and now believes that Nixon did not bomb enough — a lesson that continues to guide his “no surrender” foreign policy. R.W. Apple, the reporter who caught McCain in that thoughtful moment, eventually grew depressed at the direction of US politics and turned to food writing — including lovely appreciations of Vietnamese cuisine. Perhaps the best lessons from the conflict in Vietnam come not in reliving it, but in digesting it and moving on.

Brian Duff can be reached at bduff@une.edu.