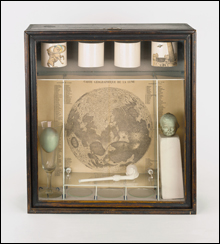

UNTITLED (SOAP BUBBLE SET): Cornell called it “the real first-born of the type of case that was to become my accepted milieu.”

|

Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) was the quintessential odd duck, meek and manipulative, a bookworm and a packrat, afraid of eye contact, scared of his own shadow, a Francophile, and a creepy panting celibate voyeur who idealized girls and mooned over Hollywood starlets and 19th-century ballerinas. He was both a recluse and a pal of art stars like Marcel Duchamp.

Still, he can seem a familiar type, haunting Manhattan shops, collecting old books, photographs, records, prints, and toys, attending the opera, theater, ballet, movies, and galleries, and then returning by train to the small home in Queens that he shared for 36 years with his disabled younger brother and domineering mother. But his motivations remain obscure. Perhaps the closest we get is a 1948 entry in his free-associative diary in which he described “complete happiness” as “quickly being plunged into a world in which every triviality becomes imbued with significance.”

Out of this stew Cornell cooked up some of the most bewitching art of the past century. Opening this Saturday at Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum, “Joseph Cornell: Navigating the Imagination” assembles 180 of his dreamy collages and signature glass-fronted shadow boxes, including 30 works that are being shown for the first time. Organized by the museum’s chief curator, Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, this terrific exhibit, the first survey of Cornell’s work in 25 years, seems an odd — but welcome — turn for a museum usually devoted to Yankee maritime trade. Chalk it up to Hartigan, a Cornell expert, who came to the Peabody Essex in 2003 from the Smithsonian, where the show premiered last fall.

The exhibit opens with Cornell’s earliest known surviving work, a tiny 1931 collage of a schooner with its aft sails sprouting a giant rose with a spider web at its heart. It’s a sharp piece — particularly the way Cornell rhymes the lines of the web with the lines of the sails — but like many of his collages, it seems generically Surrealist. It’s his boxes that distinguish his work. And he arrived at his distinctive style early, as you can see in a 1933 box that offers his typically artful arrangement of cubbyholes, a picture of a ballerina, and an assortment of mundane dime-store toys, trinkets, and mirrors.

Cornell’s first full-blown masterpiece is Untitled (Soap Bubble Set), a box he created for the 1936 Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism.” He called it “the real first-born of the type of case that was to become my accepted milieu.” Four cylindrical weights hang across the top. A clay pipe sits on a glass shelf before a print of the cratered moon surface, which rises like a bubble from the pipe. A blue egg nests in a cordial glass. A blue doll’s head rests atop a white block.

Cornell composed his works with the intuitive, associative logic of Surrealism, but his art is sweeter, more earnest and playful and poetic. He complained, “I do not share in the subconscious and dream theories of the Surrealists. While fervently admiring much of their work, I have never been an official Surrealist, and I believe that Surrealism has healthier possibilities than have been developed.” In other words, this notoriously repressed artist seems determined to disassociate himself from Surrealism’s frank, strange sexuality. Regardless, he helped bring Surrealism to America, the style that served as the foundation for Abstract Expressionism.

He was also a pioneer of experimental cinema, as a loop of his films demonstrates. Rose Hobart was named after the star of the 1931 B-movie East of Borneo, which he diced and collaged back together to create his own eerie film. When he screened it at Julien Levy’s gallery in 1936, Salvador Dalí knocked over the projector in an apparent fit of artistic jealousy.

TAGLIONI’S JEWEL CASKET: Cornell taps our mind’s insistence on putting two and two together to create narratives where none exist.

|

Cornell hits his stride in the 1940s, producing a string of hits. It probably helped that in 1942 he switched from working at his kitchen table after his mom and brother had gone to sleep to a workshop he set up in his cellar. Taglioni’s Jewel Casket (1940) is a jewelry box lined in brown velvet with a necklace slung across the top and 12 glass ice cubes nested in holes in the bottom. It refers to the legend of the great 19th-century ballerina Marie Taglioni, who during a winter tour saved her jewels from the clutches of a highwayman by dancing for him. The sculpture is charged by alchemical transformations — glass to magically forever-frozen ice to jewels.

Medici Slot-Machine: Object (1942) initiated Cornell’s series of boxes appropriating Italian Renaissance paintings of aristocratic children into designs mimicking the game machines of penny arcades. A reproduction of Sofonisba Anguissola’s portrait of a standing boy is pasted in the center. Marbles, jacks, and blocks decorated with Renaissance portraits seem to tumble down each side. A compass wheel appears in a window at the bottom flanked by loose balls, blocks, and jacks in cases decorated with maps and mirrors.